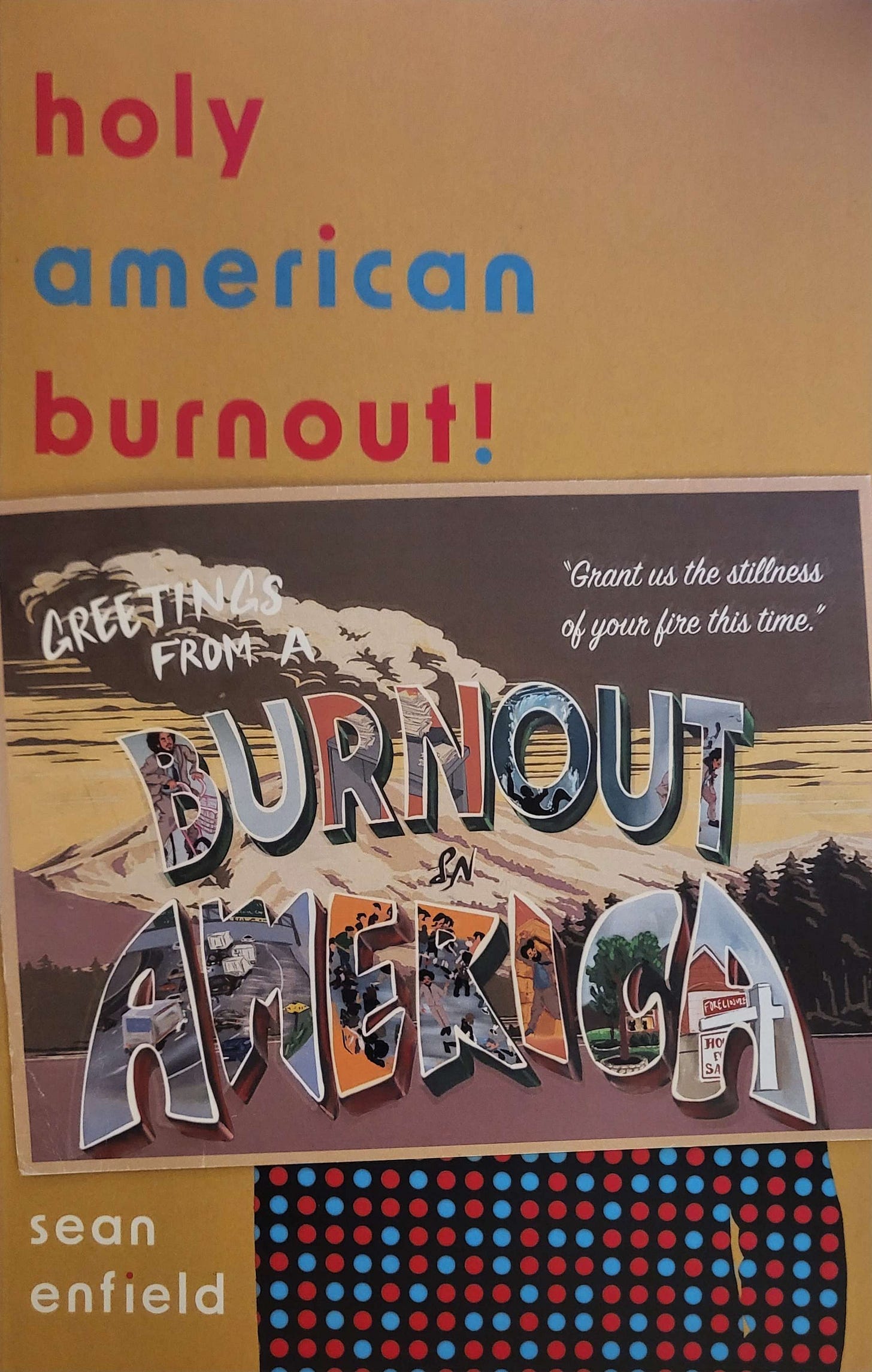

a conversation with Sean Enfield, author of holy american burnout!

a trans poetica first! in which we talk craft, resistance, and Frank Ocean

Happy two days before AWP everyone! I’m super excited to share the first trans poetica author interview with y’all!

I initially had the idea to talk with writer Sean Enfield about holy american burnout! last fall, ahead of the December pub date. But after October 7, I, like many of us, became consumed with witnessing the united states become more and more complicit in israel’s genocide of the Palestinian people. I’ve written about this in every newsletter since October, but the USCPR is a great way to get started in the movement.

A month into the new year, I still believe literature and art are pathways to liberation for all oppressed people, and I’m excited to kick off February by talking about this incredible essay collection.

Holy american burnout! largely follows Enfield’s experiences as a first year teacher here in Texas. The all-too-common burnout that educators in this country experience is explored, as well as the burnout many Black and brown folks in the united states must contend with on a daily basis.

Enfield writes the interconnectedness of a North Texan biracial upbringing, decolonial theory, middle school classrooms, musical icons, and legacies of resistance in 14 brilliant essays. How do you exist in harmful systems without furthering harm? How can our collective power keep us warm without burning us?

Burnout of course is a favorite topic of mine, and spending time with this book truly was a salve. So let’s get into it!

SG Huerta: In the opening essay, you refer to burnout as the “great American boogie man” – how did your relationship to burn out evolve or change throughout the writing of this collection?

Sean Enfield: In the most real sense, I most certainly burnt myself out in the writing of this collection. I wrote a great deal of the early draft of the collection during my time in the MFA program at University of Alaska-Fairbanks which, of course, came with a lot of the familiar trappings of grad school burnout and overextension of myself. Teaching two sections of composition, while writing the thesis, while managing the literary journal, while working in the writing center, while trying to be a human outside of all of those responsibilities. On top of that, like many, my last year in the program fell at the onset of the ongoing COVID pandemic, and the world slowed down but the deadlines did not. The grind of academia certainly helped produce, I suppose, but I’ll confess the collection that I defended as a thesis was far from polished and far removed what’s out in the world now.

By the time I had defended the collection, I wanted nothing to do with it anymore. Writing about past burnouts while burning myself out turned out to not be a replacement for therapy! So, I stepped away for a bit, and maybe rushed back into revising it too soon, but I had certainly started to see how I personally was trapped in patterns of working to the point of exhaustion, and it seemed like everybody I know was caught in that same cycle. I don’t think I knew, or still know exactly, how to break that cycle, but I wanted to at least give it a name. The pandemic itself also clarified some of that; there was a real promise in the early days that resuming from the shutdown might transform a collective burning out into a burning down of some of those systems of overwork. Of course, that didn’t happen, or at least not to the extent that some of us may have hoped, but I certainly started to conceive of burnout as a condition that, yes, wore on the body to the point of shut down but that from that idleness something revolutionary might emerge.

there was a real promise in the early days that resuming from the shutdown might transform a collective burning out into a burning down of some of those systems of overwork.

SGH: Your book recontextualizes a lot of classic (white) literature. (I will admit I really hated the number of times I had to read Romeo and Juliet in school, often opting for Baz Lurhmann’s interpretation and pretending to read it). Works such as Hamlet and To Kill a Mockingbird are given a new life for the reader in holy american burnout! I certainly felt more engaged with the tragic prince when put in the context of our tragic country. Was this something you intended to do for the reader?

SE: That is a great question, and you know, I don’t think I thought too much about spicing up Hamlet, or even Scout, in the writing of the essays. Certainly, in the lesson plans those two essays are recounting that was my goal: I wanted to make the old white literature feel a little more hip for my young brown students. Like you, and like them, I struggled to get through a lot of my assigned readings in middle and high school, but I loved reading and stories and writing, so I’d force my way through it. Seeking out connections has always been a way that I can personally muster through a book I might’ve otherwise abandoned, and so that is the spirit I bring to my classrooms and to my writing. I find that if I can make it more a conversation between life and author or author and rapper then I can usually find my way into that discussion and go from there.

I will say that I was cognizant that I never wanted to be like, “Don’t teach these old books anymore!” (well, I would say don’t teach Hamlet to middle schoolers, but I would hope that’s obvious). Personally, if I were back in those classrooms and had control over the curriculum, I wouldn’t, but teaching literature is just as much a matter of personal taste as reading it, I’ve found. I was more interested in the questions that go with teaching any books: what ways of seeing the world are you promoting with your syllabus? That for me is what the best literature course have given me—new ways of seeing. And I try to lead with a lens that is always searching and particularly searching for connection where it seemed like there was only distance.

SGH: I love that connection between syllabi and seeing the world. And it’s also a perfect segue. A few of these essays play around with form like “To Pimp a Mockingbird - A Lesson Plan,” “Teacher, Don't Teach Me Nonsense,” and “God Is a Moshpit.” Could you talk a little about the relationship between form and your writing process?

SE: Oh I love form! I am perhaps too reliant on form and have to often stop myself from just using a form for the sake of using a form. But it does, in a very practical sense, help me get started on a piece. Having a container, I’ve found, provides me with the spark to then fill that container. It is definitely beneficial to also have the right container, but that’s a matter of trying out a bunch of forms until I find the one that has the best fit.

It is always nice when that happens right at the very beginning though! That’s what happened with the lesson plan essay. The form was more the entry point than the narrative there. I knew I wanted to write about that Kendrick Lamar class I had read about and wanted to tie that into my own experience bringing Kendrick into the classroom, but it was the shape of the lesson plan that permitted that story so to speak. The form gave license to the use of second person, which is its own way of collapsing distance too, and it made it feel less like me complaining about how do you get kids to care and more about this bigger question of literacy that every lesson plan, whether explicitly stated or not, is grappling with. And then the lesson plan comes with those standard headers that acted as guideposts so that when the narrative was murky, the guidepost could drag me into the next section anyway. Certainly, my real lesson plans are godawful messes and nothing like what’s in the collection—that would’ve never made it out the slush—but the familiarity of those headers and that concept was such a freeing container.

But something like “God Is a Moshpit” though, which is a more abstract form than the hermit crab one of the lesson plan, was a much more troublesome process. I started with the conceit there, and I knew I wanted little lyrical bursts rather than paragraphs to amplify the movement, but the pendulum swinging of the paragraphs didn’t come until several revisions and several conversations (thank you to my workshop pals!) later. And even then, it was meddlesome to find the right way of presenting that back and forth that didn’t feel hokey or a little too clever—questions like how far to set the margins, what to do with dialogue, how to manage section breaks? Again, thankfully I’m a form nerd, cause that kind of meticulous playing with the page is part of why I write, but it can feel a little defeating to spend hours and hours on just playing with the margins on one page of an essay and still feel like it doesn’t look right!

SGH: Speaking of second-person, many of these essays do use the second-person POV. I think this really helps drive home the feelings of burnout and complicitness in various american systems. How do you approach POV when writing nonfiction?

SE: A lot of times it just comes out of the needs of the form. Like for the lesson plan, it just felt like it had to be second person because a lesson plan, even though it’s typically written by the person giving the lesson for the person giving the lesson, is such an instructive genre. It’s a little bit like pre-recording that voice in your head, “You need to say this now after they say that,” and so I don’t think it would have worked any other way.

But oftentimes, I think shifting the POV is a bit of cheat code for me. I’ve given up a lot of that early nervousness about “why does my story matter” that’s often the first hurdling block of writing nonfiction. Like you said in the question, we’re all entangled with each other through our american systems and what those systems do to our bodies, and nonfiction is particularly potent way of revealing the ugliness and the beauty of those entanglements. For me, shifting the POV is one way of locating that bridge. In a piece like “The Day Prince Died,” I wanted to explore my own unique experience in that moment, finding out about Prince—whose music I love dearly died—at work, through a student, at a time when I felt I couldn’t really express all the emotions that swelled up in that space, but I also recognized that probably anyone who had a deep relationship with Prince’s music likely has their own version of that story and we can find each other in our respective moments. It’s a move that the best music, film, book, whathaveyou critics are so so good at, collapsing distance in the use of a good “you” or even a well-placed “we,” writers like Hanif Abdurraqib and Roxane Gay—both of whom I was studying a lot in the writing of this book—and look, I am a terrible critic, I’m very much everyone’s mom when it comes to taking in art; I mostly just marvel at the fact that anybody is able to make anything!, but that critic voice, which often brings in the second person, can be such a strong move, and so I hope that it works as well in the narrative exploration of the art, which again Abdurraqib and Gay just excel at, as it does in the critical appraisal of the thing.

I’ve given up a lot of that early nervousness about “why does my story matter” that’s often the first hurdling block of writing nonfiction. Like you said in the question, we’re all entangled with each other through our american systems and what those systems do to our bodies, and nonfiction is particularly potent way of revealing the ugliness and the beauty of those entanglements.

SGH: A stylistic shift happens about halfway through the book; there’s an author note right in the table of contents explaining how “america– and other agents of state-sponsored violence– are written in lower case.” I’m curious to hear more about this process. First off, when the stylistic shift happens, it’s shocking just how many things are lowercase, like call of duty and pretty much every city in the lone star state. It’s very powerful in having the reader confront how empire is all around us. What was the writing process like for this?

SE: I had initially only started lowercasing those agents of violence in “All My Niggas Was white,” partly from my academic discipline reading decolonial theorists that often use the lowercasing of proper nouns as a means of de-emphasizing the self, but also it was mostly an emotional decision. Tracking my personal entanglements with national and state and local racist violence made me want to see those forces diminished in whatever way possible, but then, when I started to collect the other essays around that one, it felt disingenuous to just go back to the status quo in the next essay. So, I started applying that practice throughout the manuscript, but I had made that shift right up against the submission deadline for that window of querying before Split/Lip decided to take it on. This meant that the version that Lauren, my wonderful editor on the book!, and I worked with had a much more haphazard application of that lowercasing than what’s out now because editing is hard! And it takes time and keen editorial eye to make such a grand shift across a wholeass book, and so from our conversations, it felt like making that shift a part of the narrative would serve as a means of amplifying that throughline of burnout, coming when it does about a third of the way through the manuscript. It became a sort of tipping point narratively which then translated stylistically, and I think it helped to preserve the emotion of that shift while also clarifying the idea behind it as well.

SGH: Have you experienced pushback for this choice? If so, how have you navigated that?

SE: So far not really. I was a little hesitant to include the note in the table of contents, I’ll say, because I was worried that it might come off as justifying a decision, I don’t think needs justifying, but so far I’ve had quite a few folks that have found the note moving in and of itself which I’ve appreciated because it felt less like explaining the lowercasing of america—which doesn’t really need an explanation—and more like a tone-setter for the lens of the collection as a whole. If anybody had a problem with that, then this is likely not the book for them! And I’d hope that they’d interrogate that in themselves rather than in a lowercase “a.”

SGH: Brilliantly said. There’s a moment where you mention that most of your brain space has Simpsons quotes and Radiohead lyrics– relatable! Can we hear your favorite Radiohead lyric and Simpsons quote?

SE: Absolutely! Of course, both are always changing but right now, I’d say my favorite Radiohead lyric is “Immerse your soul in love” from “Street Spirit (Fade Out).” It’s not the kind of lyric you would normally associate with Yorke, and it even feels surprising coming at the end of that song which is such a somber meditation, albeit propulsive, on anxiety and death, but then, Yorke really chews on that last refrain, “Immerse your soul in love,” and as somebody who has grappled with my own anxiety all my life, which often manifests into fear and fascination with death, I love that sudden uplift in lyrical tone. It’s a good (necessary) reminder that for all the fixations on the darker side of life that I resort to, there’s still a way to ground myself in those I love and those who love me back. And that from the source where I usually go to wallow in those fixations!

As for the Simpsons, I am the biggest Abe Simpson fan I know, and my all-time quote from him is his “story that doesn’t go anywhere” from “Last Exit from Springfield” which gives us the great, absurd line of “So I tied an onion to my belt which was the style at the time.” But currently I love this line of Abe’s: “The good lord lets us grow old for a reason... to find fault with everything he’s made!” Which I mean, come on, that encapsulates everything I love about Abe Simpson.

SGH: One of my favorite lines from holy american burnout! is the following: “As much as I bitch and moan about people and the stupid shit they do, I am actually head-over-heels in love with humanity.” This quote is from the essay “Do You Commute?” which reminded me so much of home: dallas, mexicanos in Cowboys caps, the DART, ridiculously long commutes across the metroplex with my mom. How does living away from the dfw area impact your writing about it, or your relationship to it as home?

SE: Oh it has changed so much. I only wrote one of these essays, “Paper Shackles,” before moving away for the MFA in fairbanks. I don’t think I write the rest if I don’t move, and maybe not even if I had moved anywhere in the contiguous u.s.—“the lower forty-eight” alaskans call it, or “outside” by the real hardcore alaskans. Something about that remove (which obviously alaska is a part of the u.s. but it has its own rhythms that feel divorced from what’s happening in texas and just about everywhere else I’ve been in the country) unlocked both a nostalgia for home but also a more critical view of the dallas in which I grew up. I joked about being a bad critic earlier, but that’s only with art. I’ll criticize the hell out of a city! Living in alaska made it time-consuming and expensive to get home, so whenever I did, it was almost always a new place—dfw is an area that is undergoing constant construction (and many different gentrifying projects all across the metroplex). I still have love for it as a city in which my family and many friends still live, but I recognize now that that is tied more to the people than to the place. And people are always leaving; dallas doesn’t feel like a city where, at least the people I love there, ever seem settled, and so my relationship to the place is always changing, usually just by the simple fact of who is left in it. Maybe a part of my writing about it was a means of preserving the city as I once saw it, that which I loved and that which never seemed to love me back.

Maybe a part of my writing about it was a means of preserving the city as I once saw it, that which I loved and that which never seemed to love me back.

SGH: Reading your book was especially impactful to me as someone born and raised in and around dallas. “The Revolution Will Be Revised” is about the dpd officers that died at a Black Lives Matter protest in 2016. That night, I was staying at my elderly grandmother’s house in the city. I did not sleep– the word voyeur, as mentioned in your essay, comes to my mind too when I remember those hours on her couch scrolling and refreshing twitter endlessly as a helpless teenager. Reading this essay brought me back to that couch, that night. I’m curious about your approach to writing about something so big yet so local and personal, or if there’s anything you’d like to share about the process of revisiting that night.

SE: That’s a complicated one for sure. The initial impetus of that piece was the quickly, almost diaristic essay I wrote for Joe Milazzo’s feature in Entropy (RIP), and that one was one I wrote in a panic. I wrote it on a typewriter through anxious tears and then typed it into word with very little editing or revision. If you had told me then that I would revisit that piece, I would not have believed you.

But, once the project became so thoroughly enmeshed with my first-year teaching, it became clear that the collection wouldn’t feel complete for me if I didn’t at least attempt to go back to that piece and that night (and the following morning). Time and distance certainly eased some of the pain, but I’d be lying if I said that in revising that piece I didn’t revert into the fear and anxiety and sadness of that moment. So many of my friends were at that protest, and I just remember searching for their names online for proof that they were still posting, still alive, and hoping to not find their names as proof of the alternative. And that’s just such a painful headspace to be in, but regrettably, in this country in this world, not an unfamiliar one for most of us. I do think, however, that is a particular gift of essay writing in order to reclaim the emotion of the moment as a bridge into history or toward the reader too.

I do think, however, that is a particular gift of essay writing in order to reclaim the emotion of the moment as a bridge into history or toward the reader too.

I’m always first trying to root the moment in my own body and lived experience in hopes that that will push me toward what’s resonant about the piece, and for this essay it’s totally in that conflicted relationship with “witness,” which is tough for writers, sure, but tough for all of us now bearing witness daily to atrocities on social media. What does it mean to witness? Is it meaningful or always just gawking? These are questions I didn’t get to until I started to revise that old emotionally-driven draft, and you know, I joked earlier that this writing thing isn’t a replacement for therapy, but I do think in this particular essay it was vital for me to see what can be gained from a constant and deliberate re-engagement with what it is we are made to bear witness to and just how far removed we are from that violence (which is, of course, not very), and that’s a practice I have most certainly taken from the page and into my life.

What does it mean to witness? Is it meaningful or always just gawking?

SGH: Thank you for that thoughtful answer, and for bringing up these questions about witness. Lastly, holy american burnout! leaves the reader with Frank Ocean lyrics just before 45’s election. What are your hopes for: 1, Ocean’s music career, and 2, this country in the new year?

SE: I appreciate your tying together of Frank Ocean’s music and this country in this question. I unfortunately have given up hope for both new music from Frank and have given up hope for this country.

It has been devastating to witness the ongoing genocide perpetrated by israel against the people of Gaza, and to witness the at best ambivalence and at worst enabling response of the u.s. government. Devastating to a demoralizing degree, and it is hard to have any hope in a country that continues to aid in the destruction of a colonized people. But when I say give up hope, I don’t mean into apathy; that, to me, is the absolute worst symptom of burnout—to stop caring. I will always be invested in the prospect of new music from Frank (here is where I admit that I stayed up until 2am watching a choppy instagram livestream of his coachella “set”), and likewise, I will always be invested in speaking against the violence perpetrated by our government. In giving up hope, I have abandoned any delusion that those “in charge” will ever do what’s right—far more likely that Frank will wake up one morning and upload his hard drive to bandcamp—unless they are forcibly made to do so, and am instead focusing on what is the next right thing I can do to add to that tide toward justice, which again does not shift unless a great many people push it that way, and in what communities I can engage with in that pursuit.

But when I say give up hope, I don’t mean into apathy; that, to me, is the absolute worst symptom of burnout—to stop caring.

I will say 2024 is starting to feel like 2016 again in a lot of ways: 45 is again going to be on the ballot against a hawkish neoliberal, Frank is again making peculiar noise on the internet that may mean something but also could mean absolutely nothing (or more likely now that he’ll release some overpriced merch or jewelry), and I am again working in secondary education all the while—this time as a classroom aid rather than the head instructor, thank goodness. I have got a lotta students this time around, though, who are Frank fans, and I have been able to re-engage with his music in a new way through talking with them and that’s a gift. As long as there is an america, I will always fear the direction in which that america is headed, but I am holding onto that gift of finding solidarity through music, art, literature, activism.

What a gem of a conversation. I feel enriched and incredibly grateful to be able to share this with you all. I also hope this is the first of many more author interviews to come!1

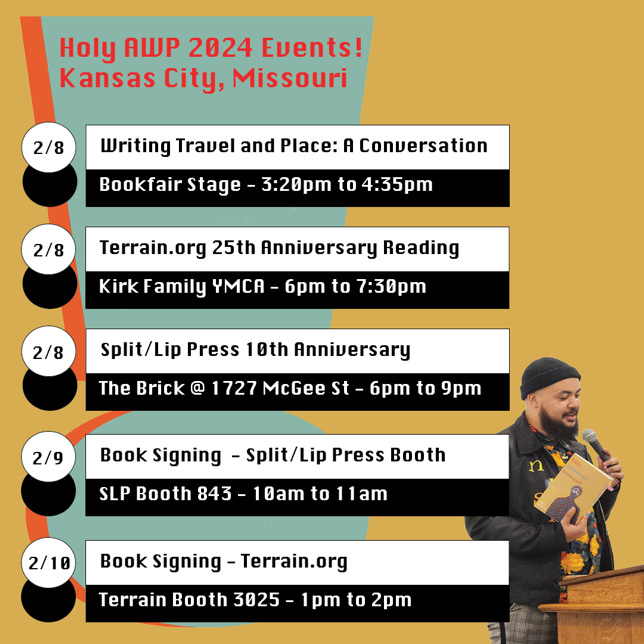

Keep on scrolling for more info about Sean, plus where to find him at AWP and beyond:

Sean Enfield is a writer and educator from Dallas, Texas. His debut collection of essays, holy american burnout!, was published by Split/Lip Press in December 2023. He received his MFA in Creative Writing from the University of Alaska-Fairbanks where he served as the Editor-in-Chief of Permafrost Magazine. Now, he serves as an Assistant Non Fiction Editor at Terrain.org. His own work has been published in Hayden’s Ferry, Tahoma Literary Review, and The Rumpus, among others, and he was the 2020 recipient of the Fourth Genre’s Steinberg Memorial Essay Prize. You can find his work at seanenfield.com, and order your copy of holy american burnout! here

Holy american Book Tour!

February 16 – Bear Gallery, Fairbanks, AK w/ Black Alaskan Art Matters

March 18 - A Room of One’s Own, Madison, WI w/ H Warren

March 20 - Deep Vellum Books, Dallas, TX w/ Chris George

March 21 - Kindred Books, Houston, TX w/ Miranda Ramirez2

March 22 – Alienated Majesty, Austin, TX w/ Diamond Braxton3

March 23– TBD, Denton, TX w/ Spiderweb Salon

Thanks for reading this far! I have three reminders for y’all: trans poetica will always be open access as a community resource, tips are always appreciated, and VIVA VIVA PALESTINA

<3

drop me a line if you have collab ideas or pitches! QTPOC to the front porfa <3

shout out to one of my fave bookstores and people

I plan to be front row cheering on Sean and Diamond!!