a conversation with Brooke Shaffner, author of Country of Under + Reading TONIGHT

"This sort of slow discussion and contemplation—deep being with the dark histories at the root of current injustices—is what literature of witness allows."

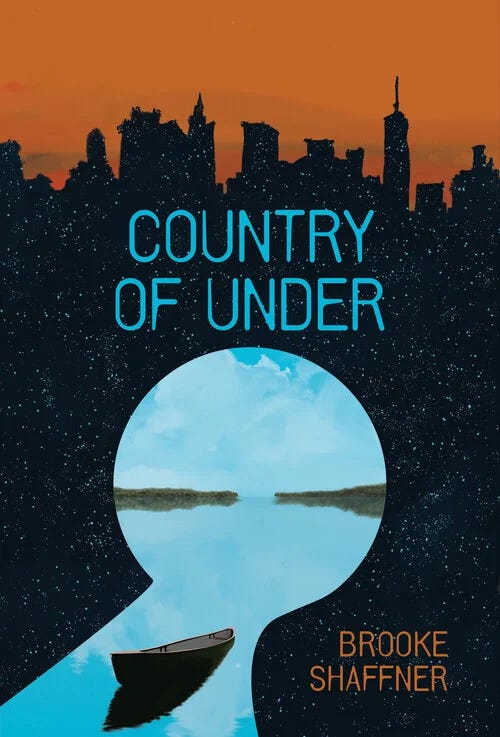

You know what today is? The official re-launch for Brooke Shaffner’s novel Country of Under with

. I’m thrilled to share my conversation with Brooke about witness, the intersections of art and activism, and writing queer border stories.Country of Under follows the intertwining journeys of Pilar Salomé Reinfeld and her friend Carlos/Carla/Río Gomez. Pilar and Carlos grow up in the Rio Grande Valley, surrounded by silence— silence around immigration, queerness, and family pasts. The novel follows the pair as they grow into themselves, face hardships, and learn what liberation can look like.

So much of Country of Under resonates with me and my multitude of identities: queer, trans, Latinx, bilingual codeswitcher. It’s a book where borders, documents, and silence are acknowledged as the impositions they are. But the book especially resonated with the part of me that’s a storyteller. Many passages in Country of Under fight back against silence and underscore the importance of storytelling, particularly for marginalized people.

Brooke and I met at the Abode Press table at AWP earlier this year. It turns out we had a few Texas connections! We continued to keep in touch, and I am so honored to share this interview.

SG Huerta: Country of Under is a gorgeous novel spanning years of resilience in different intersecting communities. You’ve also mentioned in Necessary Fiction’s Research Notes the years-long process of writing the book. How did you decide, or maybe discover, that it was a novel? I also loved all the passages in verse.

Brooke Shaffner: First, thank you for thinking so deeply about Country of Under and asking such wonderful questions. It means a lot to me that you liked the passages in verse because I’ve loved your first two books of poetry.

The first things I wrote, in college, were narrative poems. I lacked sufficient interest in poetic forms to be a poet, but the music and architecture of language has always been as important to me as story.

A visiting writer my senior year pushed me to write a memoir and my MFA was in nonfiction, but what I loved and mostly read—then and now—were novels and poetry. I’m a slow reader and can’t bear to read a book if I don’t love its sentences. My favorite novels were lyric novels by Jeanette Winterson, Virginia Woolf, and James Baldwin.

When I began Country of Under, I thought I might write a more structured lyric novel like Madeleine is Sleeping or We the Animals, with short sections that functioned almost like prose poems, but the breadth of the story I wanted to tell outgrew that tightly wound form. Still, I think my working methods might be closer to those of poets than most fiction writers. The novel came to me as a handful of pulsing images and lines, around which I slowly wove the story.

SG: I love your answer to this, because I feel the same way about sentences when reading novels. Country of Under is a very absorbing read filled with beautiful imagery and vibrant characters down to the sentence level. Can you talk a little bit about how you were able to capture settings like the Rio Grande Valley, California, and New York?

Brooke: The Rio Grande Valley was my first real home. Through elementary school, we moved every year or half-year and then when I was 11, my mom married my stepfather, whose large Mexican-American family was deeply rooted in the Valley. My Garza grandfather was an undocumented immigrant from Mexico who settled in Edinburg and had nine children. We became part of a large, tightknit, joyful Mexican-American family and community. That emphasis on family and community, on the collective over the individual, was different from what I’d come from. It’s a unique and beautiful thing.

Middle and high school, my formative coming-of-age years, were in the Valley. The scenes in the ropa usada and of night canoeing, driving past wide-open fields with music blasting through scratchy speakers, and drag pageants are built around memories. In high school, I started going with friends to our only gay bar back then, 10th Avenue, in McAllen, where the character Carlos/Carla first performs drag. We cheered on our friend Kara Juarez/Kara Foxx-Paris, who was brave enough to perform drag as a teenager in the mid-90s, against the grain of a fairly machismo, Catholic culture. Before I knew I was queer, I felt free and embraced in that space. Before I knew I wanted to write, I felt, witnessing the transfiguration of drag, what it was to be an artist—to throw open the borders of the known world.

I lived in New York City for 20 years, mostly in Brooklyn, but never adapted to winters there, so when I was able to work remotely, I spent time working and writing in the Valley during winter. I did a major revision of Country of Under there during the pandemic. I’ve worked with RGV students on their college essays for 14 years, so was steeped in their stories throughout writing the novel. My students keep me connected to the Valley and that magical and terrifying time of creating yourself as you leave home for college.

I moved to New York City straight from college, which had been in a village in North Carolina. I was 23 and was, like Pilar and Río, raw, searching, and porous. I tried to capture that free-flowing exchange between Pilar and Río’s heartbreaks and revelations and those of the city that surrounds them. I wrote Country of Under while living in Crown Heights, where Río moves the summer after their junior year, and where Pilar joins them after college. I shared Río’s infatuation with New York for a long time, and then, like a lot of artists struggling to survive there, I got burnt out. So it was fun to shift between Río proudly showing off their city and Pilar’s disenchantment with it when she first arrives in New York.

Pilar goes to college in LA, but volunteers at and becomes immersed in the world of a Carmelite monastery involved in immigrant advocacy, which becomes the primary setting during her college years. I briefly lived in LA in 2005, which is when Pilar is in college there. I set the fictional monastery in Angelino Heights, where I lived. Mark Salzman’s novel Lying Awake, about a Carmelite monastery outside LA, and Mary Jo Weaver’s Cloister and Community: Life within a Carmelite Monastery helped me to flesh out life inside the monastery. Details of the Sisters’ secret rebellions came from my hilarious cousin Claris Garza, who tried to become a nun—the activisty sort—when she was in her late 20s, but was done in by the vow of silence.

SG: Similarly, what was your approach to capturing genderfluid codeswitching ways of existing?

Brooke: My early drafts of the novel were closer to Pilar’s perspective. I wanted Pilar and Carlos/Carla/Río to be dual protagonists, but I wanted to write Río’s character with sensitivity. My incredible NYC drag advisor Marcelle LaBrecque/Marilyn Monhoe, a talented non-binary drag and musical theatre artist, made that possible. I met them on a late-night grocery store run in Crown Heights. Marcelle was doing high kicks by the checkout counter and telling their friend, who worked there, about the time that they tied their drag corset too tight and busted two ribs. Ouch, I thought and also, I’ve got to ask for an interview. I shyly approached Marcelle, who towers over me at 6 foot 7 inches, and a couple of weeks later, they met with me for a long in-person interview. I recorded and returned to that interview as I expanded Carlos/Carla’s character. Marcelle was also incredibly generous about reading through sections and answering questions that enabled me to bring authenticity to Río’s genderfluidity and drag community. It was so fun to be in conversation with Marcelle at my Brooklyn book event in May, and my partner and I are looking forward to hosting them in our new home in Charlotte when (stay tuned, NC!) Marilyn Monhoe tours North Carolina.

Just to spotlight a few other influences, I believe Alok Vaid-Menon is the prophet we need right now and I’ve been enthusiastically following them since their early days of performing. Alok’s fashion was a touchstone for Río’s. I’m a devoted listener to the LGBTQ&A podcast. I loved Sasha Velour’s memoir The Big Reveal for its expansive representation of drag as “the conjuring of a space where adherence to gender and cultural norms isn’t important.” NYC’s art and activist communities are full of folx for whom fashion is a means of challenging dominant culture. I especially loved the Queer Liberation March, which centered the voices and needs of marginalized communities.

Of course, Río is performing drag and exploring their queer identity in the early 2000s, so I needed to account for historical differences. I researched and talked with friends about when they’d first encountered gender neutral pronouns and various queer terminology. My girlfriend at the time had taken her first “gay and lesbian” (that was the language then) history class in 2006, the same year as Carlos’ class, and remembered gender-neutral pronouns being introduced. The path toward any identity that pushes against the grain of society is not a straight line, so Río’s understanding and expression of their identity evolves over the course of the novel.

SG: I love the duality of Pilar living among Sisters at a convent in California while Carlos lives among different Sisters on the opposite coast. Could you talk more about writing two characters who are chosen family, yet so different from each other?

Brooke: Even as Pilar and Río leave for college on opposite coasts and their lives diverge, parallels emerge. Romantic infatuations that end badly lead them to search for meaning. Pilar takes Introduction to Mysticism and finds purpose and community in immigrant advocacy work with the Sisters of Mother of Sorrows Carmelite Convent. Río begins to explore their queer identity in US Lesbian and Gay History and finds community performing with the Sisters of Lucky Feng’s Drag Cabaret. In shifting between Pilar finding community among nuns and Carlos finding community among drag queens, I hope that parallels emerge for the reader and the concepts of divinity, sanctuary, beauty, and transcendence expand. Pilar and Río’s differences were a way to explore false dichotomies—between contemplation and engagement, masculine and feminine, existentialism and religion, and more.

Though Pilar and Río might seem like opposites on the surface, they’ve responded to similar traumas by developing different strong suits. It’s something we often see in siblings. Pilar and Río are drawn to each other because they hold an unrealized part of each other, a buried self. Pilar must walk out of silence and isolation, and Carlos needs to move deeper into stillness and contemplation. Moving toward one another holds both the thrill and the pain of confronting that submerged self, the thrill and the pain of growth. When their lives have diverged the most, the easiest option would be to let go of each other. Choosing each other is more difficult because it demands that they step into larger selves.

As far as the writing process, I rewrote the middle section, where Pilar and Carlos are apart, during the pandemic. The story changed a lot in that fifth draft. In previous drafts, Pilar falls in love with an artist who dies by suicide. Afterwards, she goes to live with Río in New York. None of my readers cared for that storyline. Rebecca Solnit writes beautifully about activism as a love story and ultimately, I found it more interesting for activism to become Pilar’s love. As I fleshed out both Carlos’ queer journey and Pilar’s time at the convent, my writing process was parallel. I’d write Carlos’ section, inside their perspective and emotions, and then Pilar’s, inside her perspective and emotions. Close third person voice allowed me to render Pilar and Carlos’ emotions in all of their youthful fullness, while layering in the equanimity of an older perspective.

SG: I learned a lot more about the history of Central America through reading your book. How did you undertake the research for this? What were you hoping your reader would experience?

Brooke: While in college, Pilar teaches writing workshops for immigrant children at a convent. She ends up helping the mother of one of her students apply for asylum, a refugee of the Maya genocide who enters Sanctuary after ICE raids her workplace. In helping Flor apply for asylum, Pilar learns about the atrocities of the US-backed Guatemalan army’s “scorched earth” operation against the Maya in the early 1980s, which killed or disappeared over 200,000 people and displaced an additional 1.5 million.

I became interested in the original and new Sanctuary movements while volunteering with the New Sanctuary Coalition (NSC) from 2014 to 2018. In writing Flor’s story of living in sanctuary and applying for asylum, I drew on experiences of accompanying refugees to court, along with interviews with an immigration judge, two immigration lawyers, and a Catholic priest who represented thousands of immigrants in New York’s immigration courts. An interview with Ravi Ragbir, then Director of the New Sanctuary Coalition, about the New Sanctuary Movement and his experience of being held in ICE detention, was also helpful.

Volunteering with the NSC led me to research the original Sanctuary movement. I read articles and Barbara Kingsolver’s novel The Bean Trees. I interviewed a gay Episcopal priest/social worker who’d been involved in the original Sanctuary movement and attended an artist talk called Living Inside Sanctuary. Because I worked on this novel for ten years, it’s hard to remember early research sources, but I recall documentary film footage in which women spoke about their experience of living inside sanctuary.

I co-organized an artivist event focused on immigrant justice at the Brooklyn Public Library with two CUNY DREAMers, one of whom connected me to her priest, the one who represented thousands of immigrants in New York’s immigration courts. The priest, who went by Padre Bob like the priest in Country of Under, shared horrific stories of the violence against Guatemalan refugees he’d represented, which led me to research the Maya genocide.

By accompanying refugees to court, the NSC was partly trying to counter the bureaucratic coldness of the asylum process against the traumas refugees are forced to recount. I wanted, in Country of Under, to depict and work against the inhumanity of our immigration system, which is now even more restrictive.

The 1999 UN Truth Commission report on the Maya genocide, also called the Silent Holocaust, is titled “Guatemala: Memory of Silence.” A theme of personal, familial, and political silences runs through Country of Under. I wanted the reader to see those silences as connected, to see the characters working against silences in small and large ways.

As America’s dark history increasingly comes to light, conservative forces work to erase it. Just like the Holocaust, the Silent Holocaust should be taught in middle and high school. And the generations of trauma and instability that the US wrought in Latin America must be part of our discussion of immigration.

In writing about the division between churches that joined the Sanctuary movement and churches that withdrew, I was interested in the tension between contemplation and engagement, which exists in all of our lives. When I threw myself into activist projects, I was enveloped in this fiery, consuming Go! Do! energy. I struggled to transition into the quieter head space that I need to write, one that, in the words of Tracy K. Smith, “dips below the decibel level of politics.” I believe both contemplation and engagement are important to our individual and social healing. How we find the balance between them is an ongoing question in my life.

Maybe most importantly, in writing about the Sanctuary movement’s people-powered network of resistance, I wanted to insist—to borrow the words of Patti Smith, whose music figures largely in Country of Under—that “people have the power.”

SG: As you mentioned, Country of Under bears witness to the Maya genocide in Guatemala, which was committed largely by the united states and israel. What does witness mean to you now that we are ten months into a Palestinian genocide, again committed by the united states and israel? Has your relationship with the book changed because of everything we’ve seen?

Brooke: There are many entry points to Country of Under, and though I’ve spoken about the connection between the Maya and Palestinian genocide at book events and in interviews, it’s increasingly important to center that conversation, and how we can engage, which is very much on my mind. I didn’t know about Israel backing the Maya genocide, but have now read about how Israel enabled the worst of the atrocities, including the Dos Erres massacre. Thank you for making that part of this, and future, discussions.

This sort of slow discussion and contemplation—deep being with the dark histories at the root of current injustices—is what literature of witness allows. Mainstream publishers told me that Country of Under was too long and took on too much, that there were “too many novels in my novel.” At that point it was 353 pages in Word. As mentioned, I did cut a storyline, but I fleshed out Río’s queer journey and Pilar’s time at the convent, and the published book ended up being 404 pages.

In this deeply polarized time, I was interested in drawing parallels between lives that seem different on the surface. I was and am interested in conversations across differences. Staying true to my vision meant almost two years of submitting to publishers, though things sped up once I left my agent and began submitting to small presses on my own. Three years later, Country of Under has won a Next Generation Indie Book Award. They asked for a photo with the award, so I sent one in front of our Free Palestine flag. A literature of witness means insisting on your vision. Don’t let anyone tell you that your vision is too big.

Attending AWP for the first time, I met you and other activist small press publishers who are widening the space for visions that mainstream publishers won’t accept. None of the activist small press panels that my partner and I attended promised that it would be easy, but we were inspired by the beautiful, people-powered movement of thousands of small presses that we encountered.

Witness means working against erasure and numbness in my writing and though Freedom Tunnel Press, the small press my partner Niteesh and I created. And it means doing this in conjunction with local action. I had a strong activist network in Brooklyn, and I’m working on building that in my new city of Charlotte.

Witness means stretching to hold the dark and the light—the truth of violence, domination, and decimation and the possibility of reparation, reciprocity, and re-creation—all of what we have been to and could be for one another.

SG: I love your answer to the question of witness and all the dimensions it encompasses. Similarly, Country of Under feels like a love letter to activists, dreamers, and resistance everywhere. Rather than a follow up question, I want to give you space here to talk about anything you want to share related to immigration activism.

Brooke: With climate disaster, war, famine, and instability increasingly pushing migration, we need to reimagine borders and develop humane international systems of managing migration flows. Instead, Biden’s talking about shutting down the border. Lauren Markham does a great job of explaining how this militarization is not only inhumane, but incredibly expensive and a poor use of resources.

Immigrants and immigrant justice organizations need our support more than ever. One of the characters in County of Under is a lawyer for Immigration Equality, which works to secure safe haven, freedom, and equality for the LGBTQ+ and HIV-positive communities. If you’re able to donate, this organization deserves love.

With DACA blocked, DREAMers need support. Many universities have DREAMer organizations. United We Dream is a youth-led immigrant advocacy organization with chapters in 28 states.

I loved leading a writing workshop for immigrant youth at Make the Road, which is such a joyful way to get involved if you’re a writer. Make the Road is doing incredible work in the northeast and Nevada to build the power of immigrant and working class communities. They’ve organized an annual Trans Latine march for 11 years.

There are Sanctuary coalitions in many states. Here’s one in Austin where you can fight the violence and cruelty of Operation Lonestar.

If you’re near the Rio Grande Valley, the Humanitarian Respite Center in McAllen always needs help.

I love what adrienne maree brown says about making “justice and liberation the most pleasurable experiences that we can have” because pleasure is “a measure of freedom… being able to feel the erotic aliveness of a moment.” In experiences of organizing and campaigning, I got to collaborate with incredible people who inspired me, like you inspire me. I got to feel The Beloved Community. Art, literature, music, joy and connection are resistance, too. In Country of Under, I wanted to make space on the page for Pilar and Río to experience moments of aliveness—to insist that those moments are at the heart of liberation.

SG: The scenes of New York’s Freedom Tunnel in the later part of the book of course brought to mind your artivist publishing project with the same name. On the Freedom Tunnel Press site, you write “That passage [through the tunnel] birthed my novel Country of Under. I walked out of the isolation of writing a memoir and into a novel that was—sometimes overwhelmingly—in dialogue with the world.” Could you talk more about this connection and tell us more about Freedom Tunnel Press?

Brooke: I wrote more about moving from that early unpublished memoir into the research and writing of a socially conscious novel, and the role that the Freedom Tunnel played, in my Research Notes for Necessary Fiction. Listening to me struggle through my agent’s lack of communication, which dragged out the submission process, my partner Niteesh Elias had the idea to found our own press. Our manifesto will give you a sense of where I was coming from at that point.

Country of Under is a love song to artivism and the Freedom Tunnel is central to its climax, so founding Freedom Tunnel Press felt like an organic extension of the novel. Our first book, It’s Soulful and It’s Survival: A Conversation with Four Drag Artivists in the South, also happened organically. On our first visit to Charlotte, we connected with incredible artivist drag performers, who ended up performing at my book launch. Here’s an excerpt of the four-hour interview with them that we published, which offers a sense of why we felt their stories were crucial to queer history. Oso created Charlotte Latine Pride and a queer Latine entertainment company with Lolita, so these folx continue to create local history. Our friends at Scuppernong Editions told us that with the erosion of local journalism, small presses can play an important role in recording local history. This was a local book that told a larger story about resistance and possibilities for revolutionary change in America.

We conceived our next project, an anthology originally titled Shakti: Indian Artivists Resist Fascism, because Niteesh was deeply troubled by the apathy of Indian friends, family, and colleagues in the face of India’s descent into fascism. We’re now re-thinking this anthology and would like to expand our invitation to writers and artists of any background interested in submitting writing or art that resists fascism. Through this anthology, we’d like to spark cross-cultural conversations about and resistance to the international rise in fascism and rightwing nationalism. Please send us your work through the Freedom Tunnel Press website if this sounds like you!

SG: We’re going to read together at Pecantown Books & Brews in Seguin, TX to celebrate your book next month! What are you most looking forward to during your return to Texas?

Brooke: There’s so much I’m excited about as far as my Texas book tour. I’m really grateful that I get to be in conversation with you at both Split/Lip’s virtual re-launch today and then in person on September 18th at Pecantown. In talking about witness, I think of how powerfully you delve into the connections between personal and social trauma in your poetry and essays and how you work against erasure as a writer, literary citizen, and activist. Pecantown magically came through for me after months of facing small press barriers with bookstores. An Edinburg High School friend with whom I hadn’t been in touch for years connected me to the owner, Tess Coody-Anders, who I then found out had gone through Texas State’s MFA program with my nephew. Then I met you at AWP after attending a “Publishing as Activism” panel with Abode and other Texan small presses. I can’t wait to meet you and Tess in person, see my old EHS friend and nephew, and hopefully connect with some of the incredible people from Texas State’s MFA.

I’m also really excited about reuniting with my friend who performed drag in high school in the Valley, Kara Juarez/Kara Foxx-Paris, for a September 17th reading, drag show, and conversation at Alienated Majesty Books. You connected me to Alienated Majesty and I cannot wait to set foot in this miraculous bookstore and community space devoted to small press books.

My Garza family are in Texas, mostly in the Rio Grande Valley, and their stories and spirit were such a big part of Country of Under, so I’m excited about seeing them at a September 15th Rio Grande Valley Book Party at the Museum of South Texas History. I’m excited about discussing the novel in the community that birthed it.

Moving to a smaller city after so many years in New York, I’ve noticed the space for sincerity and vulnerability that’s often present at readings and art events. I’m hoping I’ll find the same eagerness to connect in the Texan cities I’m visiting.

SG: Thank you for reading my work so generously. Texas will be so happy to have you here next month! What’s on the horizon for you?

Brooke: I’m working on a memoir that explores healing, loving, and creating aliveness in this deathbed time we’re in through the experiences of my father becoming a quadriplegic when I was a child, living with the chronic illness primary sclerosing cholangitis, losing a love to cancer, and returning to the South with Niteesh.

This memoir will involve difficult conversations, so I’m interested in delving more deeply into nonviolent communication, in both my personal and political life. After more traditional campaign work, I had my first experience of deep canvassing through Changing the Conversation before the 2020 election. I’d like to do more deep canvassing for the 2024 election.

If you want to hear more from Brooke, join us and

TONIGHT at 7pm CT for the zoom launch of Country of Under!Brooke Shaffner’s novel Country of Under won a Next Generation Indie Book Award Grand Prize for Fiction and the 1729 Book Prize. The novel was the PEN/Bellwether Prize for Socially Engaged Fiction runner-up and was shortlisted for Dzanc Books’ Prize for Fiction and Black Lawrence Press’s Big Moose Prize. Brooke’s work has appeared in Scoundrel Time, The Rumpus, The Hudson Review, Marie Claire, BOMB, Litmosphere, Lost and Found: Stories from New York, Necessary Fiction, and Big Indie Books. She has received grants from the Arts & Science Council, United States Artists, and the Saltonstall Foundation and residencies from MacDowell, Ucross, Saltonstall, the Edward Albee Foundation, Jentel, I-Park, and VCCA. Brooke is bisexual and grew up part Garza, part Shaffner in Texas’s Rio Grande Valley. Her Garza grandfather was an undocumented immigrant from Mexico; her Shaffner grandfather was raised Mennonite. Brooke founded Freedom Tunnel Press with her partner Niteesh Elias to publish artivist books that straddle borders. An excerpt of her memoir-in-progress won the Lit/South Award and was nominated for a Pushcart Prize. Find more at brookeshaffner.com.

ORDER Country of Under here and check out Brooke’s newsletter here

Check out past trans poetica interviews here! Get in touch with interview/collab proposals.

Thanks for reading this far! Three reminders for y’all: trans poetica will always be free, tips are always appreciated, and VIVA VIVA PALESTINA